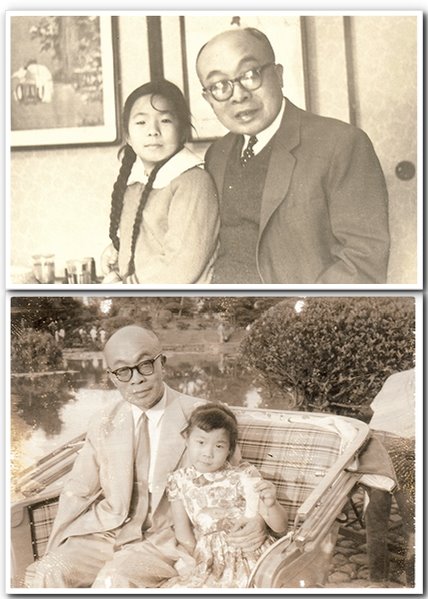

It has been 32 years since father died. I think of him often and miss him terribly. I don't like to cry in front of people. Often it's when I'm driving home after work that I let my sadness flow thinking of him. I was born when father was 53, and we had only 22 years together. Looking back, I realize how little I knew about his life. Some years ago at a book fair in New York, I found a few volumes of "Notable People of the Republic" published by the Biography Magazine and was surprised to find a biography of father written by Yao Song-Lin. From reading that article, I learned about a big part of father's early life, of which I knew almost nothing. Last year in Taipei, mother gave me bags of father's old photos. I was shaken by hundreds of yellowed black & white photos. So father was once young. I saw photos of him in the 1920's while studying in the United States, visiting friends, boating on a lake, and back in China posing next to a lily pond with his first wife and their three children. I see father looking back at me from the photos but that was a life so far, far away from me.

My father, Chin-Jen Chen, was born in 1900 in Congqing County, Sichuan Province. His education began in a traditional private village school studying classical Chinese literature. With the ending of Qing Dynasty and the founding of the Republic, father, then 11-years-old, had to cut off his cherished braided queue tied at the end with a red string, and he secretly cried his eyes out in bed over the loss. Father went to Beijing in 1913 to attend Tsing Hua School (equivalent to today's junior high school, and owned by Tsing Hua University). While attending Tsing Hua, he became the editor of the English school newspaper, which was published weekly, completely hand-written on one large page. This experience probably laid the foundation of father's career in journalism.

1919 was the year of the May Fourth Movement. The nation was boiling with rage and college students from all over Beijing responded with passion. Father joined the protest and marched in the demonstration, and was arrested and detained for several days. In 1921 there was a drought in Northern China and he was a member of the team of Tsing Hua students who went to Hebei Province to help the drought victims. After graduating from Tsing Hua University in 1922, father traveled to the United States to study at the University of Missouri, School of Journalism, where he received his Phi Beta Kappa. He then went to study at Harvard University, majoring in Political Science and History, and received his Master's Degree in 1926. He also did research at Ohio State University and Cornell University in the summer.

Father returned to China in 1927 and found employment with the Canton Provincial Government, followed by teaching positions in Shanghai at Daxia University and Fordham University. While in Shanghai, he and his Tsing Hua friends started a weekly newspaper expressing the intellectuals' views on China and World affairs. Lin Yu-Tang, who was a professor from Tsing Hua, joined in and wrote a column called "Little Critic", and the publication gained further prestige. In 1929 father went to teach at Guangxi University but resigned the following year as a result of the political unrest in Guangxi, and went to teach at Northeastern University in Shanyang. When Japan invaded China in 1931, father took his family and moved south. After teaching at Beijing University and Nankai University, father was hired in 1935 by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs to be the Editor of the English-language newspaper, Hankow Herald. While the Japanese military brutalized China, father launched his relentless attacks against the Japanese in his editorials with total disregard for his own personal safety since the Japanese Settlement was merely a short distance away. Hankow was lost in 1938 and the Hankow Herald moved inland with the government. Despite the endless bombing by the Japanese, father kept the newspaper going, often staying up all night working, even in air raid shelters.

The war against the Japanese invasion ended in 1945 and father left Hankow Herald to work for the Ministry of Foreign Affairs as an attaché, while teaching at Cheng Chi University and working for Central Trust as an advisor.

Father moved to Taiwan in 1949. Like many people in those days who left everything behind in China and went to Taiwan alone, he married again and I was born. When I was five, my parents divorced and I lived with father. When I got older, father liked to tell me about his old days, but I was too impatient to listen, let alone take notes. Today, to my regret, I only remember little bits and pieces of what he told me. All I knew was that father was the Dean of the English Department and also Graduate School of English at National Taiwan Normal University. He also taught at Tamkang College and Ming Chuan Business College. In addition, father was the Chief Editorial Writer for the English-language China Post. His life before Taiwan was very vague to me.

Maybe it was fate that I saw the biography written by Uncle Yao, so that I finally learned, in my 50's, about father's life in the context of the turmoil in the last century and how rich and eventful his life was. This realization, which came so late in my life, deepened my regret, and made me miss him even more.

During the 22 years that I had with father, he really spoiled me, but he was very strict with my education. I still remember how angry father was when I flunked my first English quiz. He had been a professor of English all his life and my flunking English was the biggest humiliation for him. I studied my English very hard after that, and never let him down again. Though father spent his whole life on the teaching of English and English-language journalism, he had a solid foundation in Chinese classical literature and steadfastly professed the importance of teaching students to write Chinese in the classical style. When I was in high school, father gave me a topic each week for me to write two short essays, one in English and the other in classical Chinese style. He would make all the corrections in red and explain to me in detail. After that, I had to write the corrected essays over again. Back then I moaned and groaned about the extra work, but now I know how much I could have learned from him. Father was not a wealthy man, but no money in the world could buy what he was able to give me. I didn't understand then what father was trying to teach me and failed to appreciate it until now, way past the middle of my life. All I can do now is to miss him and occasionally see him in my dreams.

Father was a smoker, first cigarettes, then cigars & pipes. When I went home after school everyday, I was greeted with the aroma of tobacco. To this day, wherever I am, a whiff of that aroma always fills me with warmth and longing.

One of my most prominent childhood memories is the monthly get-togethers with father's two dearest friends, Durham Chen and C. M. Sun. The three of them met for lunch or dinner once a month and brought their families along. Those were such joyous occasions. This started when I was in kindergarten and all through college. After Uncle Sun moved to the U.S., father and Uncle Chen kept up the monthly ritual. One day father and I waited and waited in the restaurant and Uncle Chen never showed up. We later learned that he suddenly fell ill and was rushed to the emergency room. Uncle Chen stayed in the hospital for two months, and father visited him after dinner every single day.

While I was in high school, father sat me down several times to make me memorize his safe deposit box number and where he kept the key. This talk filled me with fear. I knew he was putting his affairs in order and I really didn't want to listen, because listening meant I accepted the fact that one day he was going to leave me forever, but he made me listen. One morning during my junior year in college, father could not stand up and was rushed to the hospital. He was worried about the editorial he was yet to write for China Post and told me to get Uncle Chen to the hospital. After discussing for a while, Uncle Chen went home to write the editorial. Father was in good spirit and said he wanted to go home the next day. A few hours later, he died. From his passing to his burial, I did not shed a tear. I felt empty, numb, and lost.

Writing about father many years later, I am no longer the little girl running after him but not knowing much about him. I have finally crossed over the gap of time and walked into his life.

|